Tag: shisler’s cheese house

Healthy Eats: Bocconcini Salad With Figs & Pears

Making cheese is a simple process. Take some fresh milk and heat it up to 45-50 °C, add an acidic component like lemon juice to curdle the milk, strain the off the liquid whey and you have cheese. This process has remained unchanged since the beginning of cheese-making time.

Scientists have analyzed the residual fatty acids found in unglazed pottery discovered from around Europe. The results showed that humans have been making and consuming bovine based cheese products for more than 7,000 years. The pottery, which is perforated, is believed to have been used as a cheese sieve or strainer.

Seven thousand years ago we were beginning to smelter metal, invented the wheel and for the most part the human populace was lactose intolerant. Lactose intolerance happens when the small intestine does not make enough of the enzyme lactase. This enzyme is essential in the digesting of lactose, a naturally occurring sugar present in all dairy products.

Somehow we had discovered that the cheese-making process allows for maximum nutrient absorption from the milk while drastically reducing its lactose content, allowing the lactose intolerant populace to consume it without getting sick.

True mozzarella cheese is made from buffalo milk curds kneaded and pulled while repeatedly dipped in hot whey. They are hand shaped into tennis-ball sized bals. This process yields a cheese that has a spongy texture that easily absorbs the flavours of other ingredients.

These cheese balls are then packaged in salted whey to preserve them. Clearly I’m not speaking about the rubbery blocks of North American, factory produced mozzarella. When the mozzarella is shaped into smaller balls it’s known in its singular as bocconcino or its plural as bocconcini, which translates to little mouthfuls in Italian. In essence, bocconcini are small pieces of fresh mozzarella.

Goat’s milk is slowly becoming more popular in Canada, mostly due to the increase in those individuals who are lactose intolerant. Although goat’s milk is not free of lactose, it does have less than cow’s milk, making it easier to digest.

As well, goat’s milk forms a softer curd and does not need to be homogenized, as the fat globules are small and well-emulsified, which means the cream remains suspended in the milk instead of rising to the top, as in raw cow milk, once again making goat milk easier to digest.

So what happens when we make bocconcini from goat’s milk? We get a soft textured cheese that is easy to work with and has an exceptionally reduced amount of lactose, and who better to make this cheese than the Kawarthas’ very own Crosswind Farm?

I suggest trying this week’s recipe provided by Judy Filion, a Crosswind Farm employee and up-and-coming area chef.

Baked Bocconcini with Fig and Pear Salad

- 1 pound Crosswind Farm Bocconcini

- 1 ½ cups bread crumbs

- 10 roasted figs, cut in half

- 2 pears, cored and sliced in thin wedges

- 2 lbs arugula or mixed greens

- ¼ cup toasted almonds

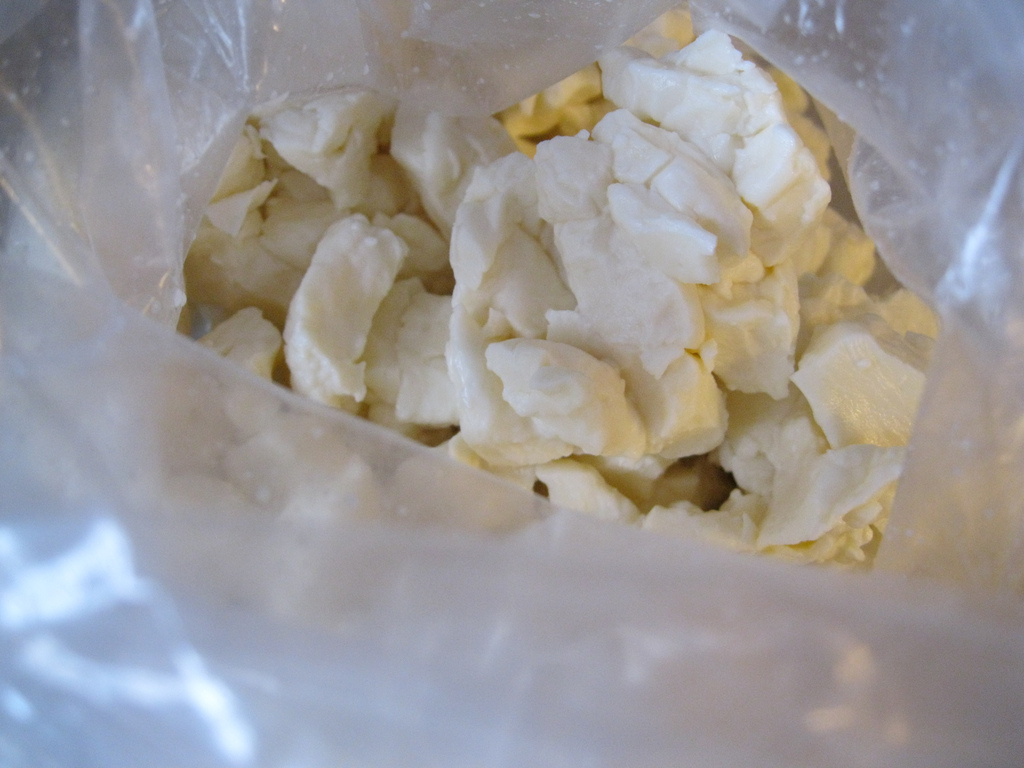

Drain the bocconcini of its excess oil and liquid. Place bocconcini and bread crumbs into a plastic bag and gently massage the bread crumbs into the bocconcini. Spread the bocconcini onto a parchment lined baking sheet and let them rest in the refrigerator for 2-4 hours.

In a preheated oven, bake the bocconcini at 450°F oven until lightly browned, about 7-10 minutes. Remove cheese from oven and allow it to cool down. While the cheese is cooling prepare the remaining salad ingredients by gently grilling the figs on a barbecue or roasting them in the oven. In a medium-sized bowl toss the leaves with a bit of balsamic vinegar and olive oil. Dress the top of the salad with bocconcini, figs, pears and almonds and serve immediately.

Yields: 4-6 portions

Mozzarella: The Papa Of Fresh Cheese!

Mozzarella is a very famous fresh cheese, made from goat’s milk, cow’s milk or in some cases, buffalo’s milk by means of an intricate and complex process by the name of “pasta filata method”. Originally from southern Italy, its name is quiet common for many different types of Italian cheeses made using “spinning” and then “cutting” this original pasta coming from milk : The Italian verb “mozzare” means exactly “to cut”.

Some common and famous types are:

- Buffalo mozzarella made from domesticated buffalo milk;

- Mozzarella fior di latte (or simply Fiordilatte) is made from fresh pasteurized, or also unpasteurized, cow’s milk:

- Low-moisture mozzarella, which is made from whole or part skimmed milk, and widely used in the food-service industry;

- Smoked mozzarella (affumicata) called in this way for the treatment that is receives which gives it a very particular and special smell and taste;

Fresh mozzarella is usually white in its common visual expression, but this colour can vary seasonally to a very mild yellow depending on the specific diet with which the animal is fed. It is a semi-soft cheese and traditionally served the day after the production, but can be kept “in brine” for a week or even more if sold in vacuum-sealed packages. Low-moisture mozzarella can also be kept refrigerated for up to a month. It is also used for many types of pizza and many very famous and tasty pasta dishes (Cooking Mozzarella) but it can be also served with slices of tomatoes and basil in the very typical “insalata caprese”.

History

A bufala is a female water buffalo. Hers is the milk – rare and expensive – from which mozzarella is traditionally made. These days, however, you’re more likely to find a version made from cows’ milk, which is more readily available and much less costly.

The history of mozzarella is closely linked to that of the water buffalo. How and when did the animals arrive in Italy? Some say it was Hannibal, others talk about Arab invasions and still others say that India was the source. What we do know is that they began to be raised in the 12th century, at a time when many peasants, fleeing war and invasions, abandoned their land. That land turned marshy, which is exactly what water buffalo like. Several centuries later, northern Italy became concerned about cleaning up the marshlands, and in 1930, the south began a massive agrarian reform. The herds of water buffalo, the “black mine” that produced “white gold,” dwindled. Cow’s milk began to replace bufala milk in the recipe. Then, in 1940 the Nazis destroyed the remaining herds. After the war, water buffalo imported from India were reintroduced to Italy, but the cheese introduced to North America by Italian immigrants in New York at the turn of the 20th century and in Canada around 1949 was made with cow’s milk.

Aside from the milk, mozzarella’s other distinguishing feature is its stringy texture. After the whey is discarded, the curds are “strung” or “spun” to achieve the characteristic pasta filata. The cheese is then cut (in Italian, mozzare means to cut), immersed in water to firm it up, then covered in a light brine, in which it is kept until it is eaten.

Etymology of the name

The name was mentioned in a cookbook witten by Bartolomeo Scappi in the 1570: “milk cream, fresh butter, ricotta cheese, fresh mozzarella and milk” (…).

The name comes from the Neapolitan dialect (from Naples, the capital of Campania) and it is the diminutive of “mozza” which, as we saw, means “cut” or, if you want from the verb “mozzare” (to cut) and it rappresents the technique of working the pasta coming from milk.

A very similar cheese is “Scamorza” which probably derives from scamozzata which leterally means “without a shirt”, reffered to the appearance of these cheeses “without” hard surface covering typical of many other dry cheeses.

Types

“Mozzarella di bufala campana” as mentioned before is a specific quality made from the buffalo’s milk: these are raised in specific areas of the territory of the regions of Lazio and Campania (Italy).

Unlike other types, that can derive from non-Italian milk and often semi-coagulated milk, the buffalo mozzarella holds the status of “Denominazione di Origine Protetta” (protected designation of origin – PDO 1996) under the European Union, While in 1996 mozzarella was recognized as a Specialità Tradizionale Garantita (STG) which translated means “Traditional Speciality Guaranteed”.

Fior di latte or simply Fiordilatte is a mozzarella made only from cow’s milk (not from buffalo). The quality of this product is inferior compared to the one from buffalo and as consequence also the price of this type of mozzarella is lower. It is for this reason that is always important the certification of the label because, especially abroad it is not unusual to find “mozzarella” not clearly labeled as deriving from buffalo made instead from cow’s milk.

Composition

You can find two type of Mozzarella: fresh or partly dried.

- The fresh one is usually shaped into balls that weigh 80-100 grams, for a diameter that usually is not more than 5- 6 centimetres. Specific brands can nevertheless make balls that can reach 1 kilogram for or about 10-12 centimetres in diameter. This fresh version is usually soaked in salt water (brine) or whey, rarely with the addition of citric acid;

- The partly dried mozzarella is more compact and dense, usually used to prepare dishes cooked in the oven, such as “pasta al forno”, pizza, etc.

It is possible to twist the “pasta filante” with the result that the final shape is a plait: this type of mozzarella is called “Treccia”. and it can have many length according to the final destination: Sunday 13 of June 2006 after 6 hours of work, Avellino won the Guinness World Record with the longest Mozzarella Treccia in the world – 106,16 meters. But usually the dimension is from few centimeters to few decimeters.

An other interesting and very typical type is the so called “Mozzarella affumicata” which is a is smoked varietes, very tasty and with a light brown collor due to the smoke that is on the surfice of the cheese.

“Nodini” is an other type of mozzarella: the term means little knots and in fact he shapes is made by weaving once the “pasta filante” and the dimension is typically around 3-4 cm. Similar to bocconcini, but a unique knot shape, this cheese gives a nicer texture and ability to expose more surface with about the same volume.

“Mozzarella Sfoglia” , literally “mozzarella sheet” is a cheese inspired by traditional puff pastry; especially in Puglia, it is the traditional base for the preparation of sweet and savoury recipes, stuffed to create original hot and cold dishes.

Several variants of mozzarella are specifically formulated for pizza: “Cooking Mozzarella” is a low-moisture Mozzarella cheese: as you can understand it contains less water than real one”.

Mozzarella can be shaped in very particular ways and artistic shapes such as elephant, pig, dummy, which are widely produced in Southern Italy: the aim of this idea is to distract where possible kids from eating junk food/candies and so for snacks and focusing on high calcium and healthy cheese instead but keeping the fun and interest high.

“Burrata” meaning “buttered”: it is a dreamy fresh cheese that consists of a Mozzarella pouch, rather than a ball, filled with a delicate milky-mousse. When you bite into it, the fillinggently oozes out. Delicious!

Stop into Shisler’s Cheese House and pick up some of your own Mozzarella!

Feta: It’s All Greek To Me!

The History of Feta

Feta literally means slice

The history of cheese has been around since the birth of humanity, and is connected to the taming of domestic animals over 10,000 years ago. The roots of cheese making are not known with certainty, however, it is believed that cheese was first produced roughly 8.000 years ago. It is very likely its discovery was completely accidental, during transport of milk in stomachs of young animals.

To the modern consumer, the word Feta means brine cheese, produced in Greece, using specific technology from sheep and goat milk. According to Greek mythology, the gods sent Aristaios, son of Apollo, to teach Greeks the art of cheese making.

There are many records regarding production and consumption of cheese in ancient Greece, from Aristoteles, Pythagoras and other ancient comedy writers. It has been known at least since Homer’s time. The cheese that was prepared by Cyclope Polyfimos and described in the 8th B.C. century in Homer’s Odyssey, is considered to be the ancestor of Feta:

“We entered the cave, but he wasn’t there, only his plump sheep grazed in the meadow. The woven baskets were full of cheese, the folds were full of sheep and goats and all his pots, tubs and churns where he drew the milk, were full of whey. When half of the snow-white milk curdled he collected it put it in the woven baskets and kept the other half in a tub to drink. Why my good ram are you the last to leave the fold? You have never been left behind by the flock before. You were always first walking ahead to graze the tender sheets of grass.”

According to myth, Cyclope Polyfimos was the first to prepare cheese. Transporting the milk that he collected from his sheep in skinbags made of animal stomachs, one day he realized to his great surprise that the milk had curdled and had taken a solid, tasty and conservable form.

In the museum of Delphi, a statuette of the 6th B.C. century can be found that depicts the exit of Ulysses hanging under the Cyclopes favorite ram. 8,000 years later the way Feta is produced remains much the same, differing only in areas such as automation and packaging.

The ancient Greeks called the product that emanated from the coagulation of milk “cheese”. The name Feta, literally meaning “slice,” originated in the 17th century, and probably refers to the practice of slicing up cheese to be placed into barrels—a tradition still practiced today. The name Feta prevailed in the 19th century, and since then has characterized a cheese that has been prepared for centuries using the same general technique, and whose origin is lost in time.

In the 20th century a mass immigration of Greeks to various countries took place mainly to Australia, the United States, Canada and Germany. As a result, numerous Greek communities were formed abroad, whose members maintained to a large extent their dietary habits. Thus, new markets were created for Feta cheese in different parts of the world, resulting in the growth of Feta’s international trade.

Feta really is Greek

The European Commission has instituted the protection of the geographical origin of various products, through their characterization as products of Protected Designation of Origin (PDO).

The European Commission has instituted the protection of the geographical origin of various products, through their characterization as products of Protected Designation of Origin (PDO).

In today’s globalization era, safeguarding origin names and the right to use these against producers providing the markets with imitations is not an easy process. Insofar as a specific product is connected in consumer minds to a specific name place, in a way that a mere mention of the product name, brings its place of production immediately to mind, it is fair and in accordance to international treaties to protect its origin name.

Initially Feta was established according to the regulation 1107/96 as a product of Protected Designation of Origin based on the terms laid out by EU regulation 2081/92 regarding the conditions for a product to be characterized as such. However, some member states appealed to the European Court for the annulment of this decision. Their position was that the name Feta had become a common one. The European Court decided the partial annulment of the regulation 1107/96, removing the name Feta from the protected geographical indication register. The thinking behind this decision was that during establishment of Feta as PDO, the Commission had not taken into account the analysis of the situation in other member states regarding the documentation of the authenticity of its origin.

After a thorough analysis regarding the situation in member states, from which it was revealed that the origin of Feta is indeed Greek, and after a recommendation from a scientific commission, the Commission suggested the re-registration of Feta in the rule (ΕC) 1107/96. The name Feta was re-introduced in the PDO registry with the (EC) 1829/2002 ruling of the Commission in October of 2002.

A European Celebration: Cheeses From Across Europe

The science, in truth, is fairly simple. Take some milk – a cow, sheep or goat will provide just fine. Add a starter enzyme and then some rennet to separate the curds (solids) from the whey (liquid). Congratulations: you have just made cheese. Almost every one begins its life-like this. “Pretty much everything after that point is a tweak,” explains cheesemonger Ned Palmer.

So, why is there such variety in cheese’s taste and textures? “One word tells you: terroir. It all starts with the land,” says Patricia Michelson of La Fromagerie, London’s best place to try and buy artisan cheeses from all over Europe. “The climate and the soil affects the animals, the food they eat – whether that is cows grazing pasture or goats foraging. Everything affects the taste of the milk, and therefore the cheese.”

Another thing all great cheeses share is the attention of a genuine artisan cheese maker. “Everyone uses the word ‘artisan’ to mean anything now,” adds Michelson. “When it comes to cheese, I mean a small dairy, using raw, unpasteurized milk from a single herd. An artisan follows the process from pasture to table, making everything by hand. Even the starter used to begin the curdling process can be made from the previous day’s milk.” The result is almost endless variety, between countries and regions, styles, even neighbouring villages.

Now, let’s take a tour of the fascinating and intriguing world of European cheese.

Austria: Alp-Bergkäse

The family of Bergkäse, or “mountain cheeses”, enjoy one crucial benefit: cows that spend their summers on Europe’s alpine pastures. “In Austria’s Bregenzer Wald region, these cheeses are made in summer only, in little chalets, not dairies,” explains Patricia Michelson, who also wrote the cheese lover’s bible, Cheese: The World’s Best Artisan Cheeses (Jacqui Small, £30). “The milk is heated in a cooper vat with wood burning beneath. Sparks fly and cinders drop into the vat – the flavour of the resulting cheese is richly wood scented,” adds Michelson.

Buyers for Michelson’s cheese business don hiking boots to source the best cheeses from the Alp Loch. Travellers can also visit cheese makers, alpine markets and specialist vendors as part of the Bregenzerwald Käsestrasse trail.

Belgium: Fromage de Herve

Belgium’s only Protected Destination of Origin (PDO) cheese is a cow’s milk cheese, made east of Liège since the 13th century. Like many made close to Europe’s west-facing coasts, the cheese is encased in an edible washed rind.

“Over-saline climates can ruin hard cheeses like cheddar. Rind washing began as a precaution against that,” explains Jon Thrupp of Franco-British cheesemonger Mons. “It takes maturation to the next level. Washing the cheese in brine kills moulds and creates an environment to promote a bacteria, B. linens, with more visceral, grassy flavours.”

Away from the coasts, monastic cheese makers often wash cheese rinds with distillates or even beer, another Belgian specialty that makes the perfect partner for creamy, yellow-hued Fromage de Herve.

Bulgaria: Tcherni Vit “Green Cheese”

The sheep’s milk cheese made in the Balkan village of Tcherni Vit gets its nickname from a mould. After shaping, salting and stacking in barrels made from lime wood, the brine-soaked cheeses are exposed to the air in a moist cellar.

That’s when the magic starts to happen. A green mould forms quickly on the cheese’s surface, and often also penetrates veins that form naturally during maturation.

Croatia: Paški Sir (Pag Cheese)

Croatia’s Dalmatian coast is the country’s holiday hotspot. Yet one of southeastern Europe’s most prized cheeses is also made here, on just one island: Pag.

A salty, dry winter wind, the Bura, lends the hard cheese a sharp saline bite, as well as its distinctive flavour. “This wind brings sea salts to the pastures from the Adriatic Sea, which covers the unique wild herbs that our indigenous breed of sheep eat. The result is a very high fat milk from which Paški sir gets its distinctive taste,” explains Simon Kerr of Sirana Gligora, a Pag Cheese producer.

“Aged Paški sir, or stari Paški sir, is a minimum of 12 months old and generally has a deep brown rind and crumbly texture. The taste is fuller with a strong, long finish.”

England: Blue Vinny

England’s rural southwest is home to many fine cheeses. Crumbly, blue-veined Blue Vinny has even inspired poetry in its home county, Dorset. “The recipe lay dormant for many years until Mike Davies resurrected it at Woodbridge Farm and started producing this unique blue cheese again,” says Steve Titman, executive chef at Summer Lodge, a Dorset country house hotel known for its 27-variety cheeseboard.

Compared to more famous English blue cheeses like Stilton, Dorset Blue Vinny is lighter and milder, usually with a lower fat content. “Even when very blue the flavour is not overpowering — a tingle rather than a tang,” adds Titman.

France: Valençay

How do you select just one variety from Europe’s most famous cheese-producing country? “The French are unmatchable when it comes to soft goat’s milk cheeses,” says Jon Thrupp. France’s goat cheese heartland is the Loire Valley, an easy drive southwest of Paris. “Lactic cheese making is probably the oldest style in Europe,” says Thrupp. “It is close to what happens naturally when you strain yogurt: lactic acids slowly cause the curds to set, in a process taking around 24 hours.” Hard cheeses like Comté, in contrast, are set with rennet in around 2 hours.

Valençay owes its unusual “decapitated pyramid” shape to its setting mould – the optimum dimensions for draining – not because of an apocryphal, yet often repeated, tale about Napoleon, according to Thrupp. Its taste, “velvety, rather than fluffy or brittle, with light, citrus acidity,” is enhanced slightly by rolling the young cheese in ash. The ash lends it a “slightly pointed, white pepper flavour,” says Thrupp.

Germany: Bavarian Blue

Bavarian Blue is sometimes nicknamed “mountain Roquefort”, due to a similarity with France’s famous blue. The style was invented in 1902 by Basil Weixler, who loved Roquefort. Its production involves mixing the same moulds (roqueforti) with the curd.

But Bavarian Blue is made from cow’s milk, rather than Roquefort’s sheep. The best Bavarian Blue is smoother and creamier than its French cousin, and mild enough to eat at breakfast. Michelson recommends Bavarian Blue made by Arturo Chiriboga at the Obere-Muehle Co-op, where they is also operate a hotel and guesthouse.

Greece: Feta

Grainy and crumbly, feta cheese is made from either sheep or goat milk, and aged for 2 months or more before sale. Travellers know it as a key ingredient in Greece’s best-known dishes, among them Greek salad (leaves with tomatoes, olives and feta) and spanakopita (cheese and spinach filo pastry pie). The cheese has a unique place in Greek culinary and cultural history. “It dates back to Homer’s day,” explains Manos Kasalias from the Association of Agricultural Cooperatives of Kalavryta.

Feta is produced in several regions of Greece, including Macedonia, Thrace, Thessaly and the Peloponnese. “The best feta carries with it the aromas of the Greek mountains that the sheep and goats graze,” says Kasalias. “The curd isn’t boiled or baked at high temperatures and, both during the production process and afterwards, the cheese is protected by a light brine, locking in all those flavors.

“The best feta is produced from late April to mid-June when the flora on which the flocks graze is richest.”

Ireland: Milleens

Washed-rind cheeses are a staple of the cheese making landscape in County Cork. Alongside Milleens – which blazed a trail for Irish artisan cheese in the 1970s – are names such as Ardrahan and Gubbeen. “The wet, salty climate lends itself to this style,” says Ned Palmer, a freelance cheesemonger and expert in the cheeses of the British Isles. “In fact, it’s hard to make any other style there.”

Before maturation, the cheeses are washed in brine, which encourages the formation of a sticky, bacteria-friendly rind and a distinctive smell. “Milleens tends towards the heftier end of the taste spectrum,” says Palmer. “It is meaty and pungent, with an unctuous, creamy texture. For me, it is one of the few cheeses that works with a big red wine.”

Italy: Parmigiano Reggiano

The iconic cheese of Italy’s Emilia-Romagna region is more than just an accompaniment to a bowl of pasta. “It might seems like a trivial, obvious choice,” says Piero Sardo, President of the Slow Food Foundation for Biodiversity. “Yet only if you don’t know that this large production, of around 3 million cheeses, hails from over 500 small artisan dairies that must meet a very strict regulatory regime.” Parimgiano Reggiano rules stipulate a minimum of 12 months’ aging, but the cheese can improve for up to 3 years, according to Sardo. The consortium that governs cheese production here also operates guided tours of dairies across Emilia-Romagna.

Netherlands: Beemster

Beemster polder in North Holland was drained by dyke and windmill in the early 1600s, one of the first reclamation projects of its kind in the Netherlands. It’s now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and signs of humans shaping this unique landscape 20 feet below sea level are preserved everywhere.

It is also mineral-rich farmland, and only cow’s milk from Beemster herds goes into its famous cheese, which has been made here since 1901. “Beemster X-O is our most mature cheese in the line and aged a minimum of 26 months,” explains Kies Paradies at Beemster. “Over time, Beemster X-O develops aromas of butterscotch, caramel and whiskey.”

Norway: Geitost

Geitost (pronounced “yay-tost”) is made by an unusual process. After removing the curds, the cheese maker boils down the whey with a little added goat and cow’s milk cream. A Maillard reaction turns the mixture brown, imparting a sweet, caramel-like flavor to the cooled cheese. When sliced open, it looks like a bar of chocolate. “It is popular with kids in Norway,” explains Michelson. “Sliced very thin, more like a shaving, and spread on some rye toast.”

Geitost has been made in the traditional way for hundreds of years alongside Norway’s largest fjord, the Sognefjord. Six cheesemakers are now recognized by Slow Food for the production of genuine artisan Sognefjord Geitost. These days, the area is one of Norway’s most scenic fjord cruising spots.

Portugal: São Jorge

It is unusual to find a Portuguese cow’s milk cheese. Yet the milk isn’t the most striking thing about São Jorge. This waxy, tangy, cheddar-like cheese is made well beyond mainland Europe. It comes from the mid-Atlantic, in the Azores archipelago, 900 miles off the coast of Portugal.

Flemish colonizers brought cheese making skills to the Azores in the 17th century. The island’s high humidity, volcanic soils and year-round warm – but not excessively hot – temperatures are ideal for milk-producing herds. The cheese, however, is made only in summer.

Scotland: Isle of Mull

Scotland is not the home of cheddar cheese. But an island off Scotland’s wild west coast is where you will find one of the cheddar style’s most distinctive expressions.

“A cooler, wetter climate produces higher moisture cheese than down in England,” explains Ned Palmer. “The cheese has very distinctive flavor notes that come from a specific cattle feed: draff, the barley mash that remains from whiskey making. You can taste the peat, malt and iodine notes that you expect in a single malt whisky.” This makes the cheese an ideal partner for another Mull artisan product, Scotch from the distillery at Tobermory.

Spain: Queso de la Serena

Spain’s central and northern regions are the country’s cheese-making heartland. Queso de la Serena, on the other hand, is made in small quantities in just one county of Extremadura, in the far southwest. It is made only with the unpasteurized milk of Merino sheep that graze the pastures of La Serena.

“Its quality that comes from the area’s pasture, which is full of herbs,” says Piero Sardo. “With aging, the cheese tends to become creamy and smooth, and often is called ‘cake’. It gives off scents of green grass and caramel, hints of chestnut and hazelnut, and has a slightly bitter finish.”

Sweden: Almnäs Tegel

Scandinavia las a long tradition of cheese making – long winters meant a traditional need to preserve the summer bounty. The quality of the region’s artisan cheese is high, and growing. So, why do Scandinavian cheeses often lack a high-profile outside the region? “Because of where they are made, the location. Their cheeses are difficult to get hold of,” explains Michelson. “But this is getting better, thanks to the huge interest in everything Scandinavian when it comes to food.”

Almnäs Tegel is an unpasteurized cow’s milk cheese similar in style to Gruyere and Parmigiano, aged for between a year and 24 months. The distinctive shape of a whole cheese is an homage to the bricks used to build the farm’s original manor house, in 1750. Throughout the ripening process, the 55-pound cheeses are brushed with brine. The result is a strong, hard cheese.

Switzerland: Emmentaler

“Say ‘Swiss cheese’ and most people will think of the one with holes,” says Diccon Bewes, author of Swiss Watching. Often known (incorrectly) as “Emmental” outside Switzerland, Emmentaler is made from Alpine cow’s milk in giant rounds weighing in at 265 pounds each. “Emmentaler was the first Swiss cheese to be made down in the valleys all year round in a village Käserei, or cheese dairy. That gave farmers a permanent outlet for their milk and led to much bigger rounds of cheese, because they didn’t have to be carried down the mountain in autumn,” explains Bewes.

The texture is smooth, and the flavour nutty, especially in Emmentaler that is matured for a year or more. An Emmental cheese route, complete with iPhone and Android apps for guidance, helps hikers and bikers see the region’s cheese sights.

Wales: Caerphilly

This crumbly Welsh cow’s milk cheese is part of a family of cheeses unique to the British Isles, including English varieties Cheshire, Lancashire and Wensleydale. “Caerphilly stands out from these in that a traditional example will have a mould rind rather than a cloth rind. This contributes a deeper, earthy flavour to the cheese,” says Ned Palmer, who also hosts regular cheese tastings.

According to Palmer, best in class is Gorwydd Caerphilly made on a family farm in West Wales using unpasteurized milk and traditional methods like hand-stirring of the curds. Visitors to London’s Borough Market will usually find it on sale somewhere.

Cheese Curds: Cheese’s Best Kept Secret

There’s nothing like a 4-year-old cheddar to remind us of how very great cheese can be. It’s creamy; it’s sharp; and it’s downright addictive. But as great as aged cheddars are, their polar opposite — which go by the mildly unappetizing name of cheese curd — are equally delicious yet a thousand times harder to find.

If you have the good fortune of being from Wisconsin, have indulged in Canada’s famous poutine, or have just sought these curds out on your own then we don’t have to educate you on the wonders of this food. BUT, if hearing the words “cheese curd” causes you to wrinkle your nose instead of making you hungry, you need to read on. Because, folks, you are seriously missing out.

Cheese curds are what your mouth has been missing all this time. And you might want to head to the nearest cheese maker to remedy that, like, stat. But first, here’s what you need to know.

Summer Sausage: A True Summer Treat!

Summer sausage is a seasoned sausage that is thoroughly cured and does not require refrigeration to remain fresh. There are many varieties of this sausage, including cervelat-style sausages such as blockwurst, thuringer and mortadella. People in many countries, especially those across Eastern Europe, have their own varieties of these summer sausages, dating to periods when meat needed to be well-preserved because refrigeration was not an option through salts and other natural preservatives. This food product is often available at butchers and in boutique shops that import special regional foods.

Despite its name, summer sausage is not necessarily made in the summer, although it can be. It is made with meat scraps, like all sausage, so it tends to be made when animals are butchered, which is often in the fall or spring. The sausage might also be made with a combination of meats for efficiency and flavor variety. Cuts are often kept lean to ensure that the sausage does not become rancid during the curing process.

Types of Ingredients

A common combination in summer sausage is beef and pork, although venison and other game meat might be used as well. Some of these sausages also traditionally contain organ meat, although this culinary tradition has waned. Salt is always used in the seasoning of summer sausage because it promotes a sound cure. Pepper, mustard seeds and sugar might be used as well in some regions. People from different areas have their own seasoning traditions, resulting in a wide range of flavors within this diverse family of cured meats.

Careful Curing

After the ingredients are thoroughly combined and forced into sausage casings, summer sausage must be cured. Cures for this sausage vary, with it generally being smoked or dried. Traditionally, air drying is accomplished in the open on large racks that take advantage of seasonal winds. Smoking is slowly done at a very low temperature to create an even, strong cure. Complete curing might take weeks or more than a month, and careful monitoring is needed to ensure that the sausages have not gone bad.

Preparation and Serving

After curing, summer sausage generally can be eaten straight, and it is often served cold. The end texture is semi-dry to moist, depending on the type of cure used. It can be heated or cooked, or it might be tossed with other foods. Some modern versions might be less extensively cured, requiring refrigeration and cooking before it can be used. The flavor of this type of sausage is more mild and less salty than true summer sausage.

Make Shisler’s Cheese House your next stop and pick up some of this delicious summer sausage!

Pecorino Romano: A Classic Italian Sheep’s Milk Cheese

There are two types of sheep’s milk cheese known as Pecorino in Italy. The word pecorino without a modifier applies to a delicate, slightly nutty cheese that’s mild when young, and becomes firmer and sharper with age, while gaining a flaky texture. It’s not suited for grating, and though it can be used as an ingredient, it’s best on its own, in a platter of cheeses or at the end of a meal, perhaps with a succulent pear.

Much of this kind of pecorino is made either on the island of Sardegna, or in Tuscany, by Sardinian shepherds who came to the mainland in the ’50s and ’60s, and as a result is generally labeled pecorino sardo or pecorino toscano.

Then there’s Pecorino Romano, which is saltier and firmer; it’s an excellent grating cheese, and also works well as an ingredient because it doesn’t melt into strings when it’s cooked.

In its milder renditions it’s also a nice addition to a cheese platter or with fruit, especially pears, while a chunk with a piece of crusty bread and a glass of red wine is a fine snack.

Though one might expect Pecorino Romano to be made around Rome, and perhaps in the Alban Hills, its production area is considerably wider, extending into southern Tuscany and also Sardegna, which is where the Consorzio per la Tutela del Formaggio Pecorino Romano, the organization that oversees the production of Pecorino Romano, has its offices.

Why would the organization overseeing the production of a Roman cheese have its offices in Sardegna?

To begin with, Romano doesn’t refer to Rome, the city, but to the Romans, who were already making this cheese 2000 years ago; Lucio Moderato Columella, who wrote De Re Rustica, one of the most important Roman agricultural treatises, says, “the milk is usually curdled with lamb or kid rennet, though one can use wild thistle blossoms, càrtame, or fig sap.

The milk bucket, when it is filled, must be kept warm, though it mustn’t be set by the fire, as some would, nor must it be set too far from it, and as soon as the curds form they must be transferred to baskets or molds: Indeed, it’s essential that the whey be drained off and separated from the solid matter immediately.

It is for this reason that the farmers don’t wait for the whey to drain away a drop at a time, but put a weight on the cheese as soon as it has firmed up, thus driving out the rest of the whey. When the cheese is removed from the baskets or molds, it must be placed in a cool dark place lest it spoil, on perfectly clean boards, covered with salt to draw out its acidic fluids.”

Though modern cheese makers use heaters rather than the fireplace, and use calibrated molds rather than baskets, the basic process is unchanged; the curds are heated to 45-48 C (113-118 F), the curds are turned out into molds and pressed, and the cheeses are then salted for 80-100 days: For the first few days they are turned and rubbed with coarse salt daily, then every 3-4 days, and finally weekly. The cheeses are then aged on pine boards for 5 months prior to release. The technique is very distinctive and imparts a characteristic salty sharpness to the cheese. Of course cheese comes from milk, and it’s important too; Pecorino Romano isn’t simply made from sheep’s milk, but from the milk of sheep that have grazed pastures with specific combinations of grasses that impart specific flavors to their milk.

And this brings us back to why Pecorino Romano is made in the Tuscan Maremma and Sardegna as well as around Rome. As I said, its flavor is quite distinctive, and it’s an important ingredient in many south Italian dishes. Those who left the south to seek better fortune abroad during the last decades of the 1800s and the early 1900s were forced to leave almost everything behind, but not their tastes: As soon as they settled they began to cook, and one of the ingredients they needed most was Pecorino Romano. There was no way to make it locally (different climate and forage means a different cheese, even if the production technique is the same), but what was made in Lazio kept very well — Columella remarked on this too, and because of its keeping qualities legionnaires on the march were issued an ounce of Pecorino a day to add to their porridge — so the immigrants ordered it: By 1911 7,500 tons were being sent annually to North America alone.

The cheese makers couldn’t meet this demand with the flocks in Lazio — not all pastures give the proper milk — so they searched elsewhere for pastures that would work, finding them in southern Tuscany and Sardegna.

Currently about 20,000 tons of Pecorino Romano are exported every year, 90% of which to North America.

Pecorino Romano is an excellent source of calcium, and indeed Roman wet nurses were traditionally given Pecorino to enhance their milk. It’s also a good source of phosphorous, potassium, and magnesium, and a good source of protein — a chunk of Romano is about 25% protein. It’s also 31% fat, and though this is significant, people on diets often use it to flavor their foods because a little goes a long way.

Purchasing:

Forms of Pecorino Romano are barrel-shaped and weigh between 40 and 95 pounds (18-40 kg); before release the cheese is marked with a sheep’s head inside a diamond and the rind is stamped with dotted letters spelling out “PECORINO ROMANO.” Given their size, you won’t want to buy a whole cheese, but rather a wedge; if you can, select one from the middle of the form, which will not have the bottom rind. The body of the cheese should be white with faint straw yellow overtones, and break with what the Consorzio describes as a “granitic aspect;” it shouldn’t look too dry.

When you get it home, store it in the cheese box in your refrigerator, wrapped in either plastic or aluminum foil to keep it from drying out.

Make Shisler’s Cheese House your next stop for your own helping of Pecorino Romano!

Muenster Cheese: In A League Of Its Own

It’s a dilemma many families face. The grownups want a cheese with character, flavor, and “bar-none” quality… while the kids’ idea of excellence comes in plastic-wrapped slices of questionable origin. We have a solution: Next time family grilled cheese night rolls around, reach for a cheese that everyone will love for all the right reasons. It’s mild, mellow, melts like a champ, and is actually cheese. The kids will even love its name: Muenster.

Muenster Cheese History: Where Did It Come From?

For starters, Muenster is almost nothing like Munster (or Munster-géromé) cheese from France. It also has nothing to do with the Irish province of Munster or the German city of Münster, although Muenster would seem to be an Anglicized version of the German name. Here, then is a little Muenster cheese history:

The French Munster cheese comes from Alsace, that very German region of France that has changed hands between the two countries for centuries. (The German city of Münster is just across the Rhine in Westphalia, so maybe there’s more of a connection than is believed.) It is a washed-rind cheese on the order of Limburger, first made by Benedictine monks as a way to preserve milk. While Munster doesn’t have the overpowering smell of Limburger, it is a strong-tasting semi-soft cheese with a red-orange rind caused by the bacteria that give it its distinctive flavor.

French immigrants in the 19th century first figured out how to make Muenster cheese in Wisconsin. It’s likely that they were trying to imitate the French Munster, as the American version has the same semi-soft texture; however, its distinctive red-orange rind (if present) gets its color from annatto, the same natural vegetable dye that gives many Cheddars the familiar orange hue. And the Wisconsin version tastes nothing like the Alsatian original; because it does not go through the rind-washing and aging process, its flavor is very mellow with a pleasing tang, somewhat like a Monterey Jack. Because it truly has its own identity, Muenster may be considered one of the truly great original American cheeses.

Muenster Cheese Pronunciation

Muenster is pronounced either like “munster” (with a short u like bun) or “moonster” (with a short oo like book). Young children may think it’s cool to call it “monster”…and with its orange rind it’s a nice addition to a Halloween platter.

Muenster Cheese Uses

The smooth, mellow taste of Muenster is extremely versatile and adaptable to many dishes, so naturally, there’s no shortage of Muenster cheese recipes. Slice it for hot or cold sandwiches—it goes with any cold cuts—or cut it in cubes for a cheese tray.

Because it melts so wonderfully, with the perfect elasticity, Muenster is one of the finest additions to grilled cheese recipes. And those same characteristics—along with its food-friendly flavor that complements a wide variety of toppings—make it one of the best cheeses for cheeseburgers.

Muenster Cheese Pairings

Wine:

Muenster pairs well with a variety of reds (pinot noir, Beaujolais, merlot, zinfandel) and dry to sweet whites (chardonnay, pinot gris/pinot grigio, riesling, grüner veltliner).

Beer:

Belgian ales, brown and pale ales, lagers (including pilsners), and dark porters and stouts all go well with Muenster.

Meats:

Beef, poultry

Fruits:

Apples, dried fruits, grapes, pears

Make sure to put Shisler’s Cheese House on your agenda so you can pick up some your own Muenster Cheese today!

Baby Swiss: A Delicately and Deliciously Crafted Cheese

As many know, there truly is no “Swiss Cheese” in Switzerland. In Switzerland, they make a variety of “Alpine” cheeses, with some having large holes. The most notable of these cheese is Emmentaler.  During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, many of the Swiss cheese makers began to move to Wisconsin and settled in the “Dairy Belt” of Green and Dodge Counties. Originally, they made large wheels of cheese (3 feet wide, 125 pounds) patterned after the Emmentaler of Switzerland. Naturally, these became known as ‘Swiss Cheese.’

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, many of the Swiss cheese makers began to move to Wisconsin and settled in the “Dairy Belt” of Green and Dodge Counties. Originally, they made large wheels of cheese (3 feet wide, 125 pounds) patterned after the Emmentaler of Switzerland. Naturally, these became known as ‘Swiss Cheese.’

As the trend changed to larger cheese factories, a broader market and wider distribution, the call for a smaller cheese with milder flavor began to arise. This was soon addressed with the development of this much smaller cheese made with full fat milk that was aged only a few months. Although this new cheese was not that small at 5 lbs, compared to the much larger Emmentaler cheese, it is truly a baby.

A bit of history:

The driving forces in Baby Swiss evolving into a true “made in America” style cheese, were two Wisconsin cheese makers.

The driving forces in Baby Swiss evolving into a true “made in America” style cheese, were two Wisconsin cheese makers.

They were Eldore Hanni and Alfred Guggisberg, who were both of Swiss background (as can be seen by their names here).

Eldore was second generation Swiss, living in the heart of dairy country in Wisconsin, where much of the cheese making was of Swiss and German influence. Alfred moved to Pennsylvania from his home country- Switzerland.

Alfred  Guggisberg was only 16 when he began to make cheese in the mountain pastures of Switzerland (the Alps). He furthered those skills at the famous Swiss cheese maker’s institute before coming to the United States in 1947. Here, he settled in the Doughty Valley in Charm, Ohio to work with the Amish farmers as a cheese maker. By the 1960’s, Alfred had developed a new style of cheese, which became the Baby Swiss cheese (1968). This was patterned after the Emmentaler of his homeland, but was much smaller and made with a richer milk. His focus in doing this was to develop a milder flavor for the American palate. Today, the Guggisberg cheese company is still thriving.

Guggisberg was only 16 when he began to make cheese in the mountain pastures of Switzerland (the Alps). He furthered those skills at the famous Swiss cheese maker’s institute before coming to the United States in 1947. Here, he settled in the Doughty Valley in Charm, Ohio to work with the Amish farmers as a cheese maker. By the 1960’s, Alfred had developed a new style of cheese, which became the Baby Swiss cheese (1968). This was patterned after the Emmentaler of his homeland, but was much smaller and made with a richer milk. His focus in doing this was to develop a milder flavor for the American palate. Today, the Guggisberg cheese company is still thriving.

Eldore Hanni was a second-generation Swiss immigrant, who began making specialty cheese as a teenager (he managed a cheese factory at the age of 17). His strength was developing new recipes and in the early 1970’s, Eldore began working on a recipe for Baby Swiss. Later in the 70’s, he moved to the Amish area of central Pennsylvania to establish his new dairy and work with the milk of the Amish farmers. This eventually became Penn Cheese which flourishes to this day, although Eldore has retired.

There was a similar and parallel evolution for both men in developing this cheese. It resulted in a cheese with smaller holes and a creamier flavor from the use of full fat milk. It did not need to age as long and hence had a milder flavor.

What is a Baby Swiss:

In Switzerland, there is no ‘Swiss’ cheese, because there is a wide range of Gruyere and Emmentaler style cheese. Essentially, these can be divide into those with or without holes. In America, we call anything with holes Swiss Cheese. Most of these have origins in the dairy counties of Wisconsin, where many German and Swiss immigrants settled with their cheese making skills.

The “true” Swiss cheese is Emmentaler (never called Swiss), a cheese made in Switzerland under an Appellation of Controlled Origin to ensure that the integrity of the cheese is maintained. The technique, however, has been duplicated in numerous nations, leading to generic “Swiss” cheese for sale in many nations.

The “true” Swiss cheese is Emmentaler (never called Swiss), a cheese made in Switzerland under an Appellation of Controlled Origin to ensure that the integrity of the cheese is maintained. The technique, however, has been duplicated in numerous nations, leading to generic “Swiss” cheese for sale in many nations.

But this is a Baby Swiss Cheese…

The flavor of ‘Baby Swiss’ cheese is buttery, nutty, and creamy. The cheese melts very well, making it suitable for a wide range of dishes. The small holes also make the cheese easier to work with, since especially large holes can pose problems in salads and other dishes which involve slices of the cheese. Some delis also label baby Swiss cheese as ‘Lacy Swiss,’ since the cheese looks like fine lace, but those are actually made from a lower fat milk.

How is this cheese made:

This is a cow’s milk cheese made with a mixture of bacteria. Besides the normal lactose converting bacteria, it contains another special propionic bacteria that breaks down the lactic acid in the cheese and generates carbon dioxide, which forms bubbles in the cheese as it ages. This is quite similar to bread dough rising but takes much longer.

The longer the cheese is allowed to age, the more complex the flavor gets, and the larger the holes will become.

One of the primary steps in making this style of cheese is a very slow conversion of lactose to lactic acid.

This is accomplished by:

- Controlling the amount of culture and ripening time.

- Removing whey and replacing with warm water early in the process to limit the culture’s food supply (lactose).

This will result in the very elastic curd structure, and functions to hold the gas in the cheese as the holes develop. This is most obvious in the finished cheese, with round glossy looking holes and the elastic ability to bend the cheese slices without it breaking.

This will result in the very elastic curd structure, and functions to hold the gas in the cheese as the holes develop. This is most obvious in the finished cheese, with round glossy looking holes and the elastic ability to bend the cheese slices without it breaking.

To make ‘Baby Swiss’ cheese, several things about the cheese making process are altered from traditional ‘Swiss:’

- The cheese is made with whole milk, for a richer, buttery flavor.

- It is usually a much smaller wheel of cheese, about 5 pounds.

- The use of a Mesophilic rather than a Thermophilic culture is used.

- The milk may also be cut with water, which slows the bacterial activity.

- Most importantly, Baby Swiss cheese is aged for a very short period of time, so that the holes do not have time to grow very large. The shorter curing time also results in a more mild flavor, which some consumers prefer.

Be sure to stop by Shisler’s Cheese House and pick up some Baby Swiss Cheese on your next stop!

Chicken Paprikash: Old-Fashioned Never Lost Its Touch!

When 16th century explorers began sending new foods back from the Americas, it was as if a giant cornucopia had been emptied over Europe. Italy and Spain made tomatoes a staple of their cuisine, potatoes found a home in northern Europe and Turkey began raising and exporting red peppers, which the Hungarians found a perfect match for their soil and, eventually, their cuisine. The peppers’ odyssey eventually lead to Hungarian paprika and Hungarian paprika lead to one of the world’s great peasant dishes –Chicken Paprikash.

What is Chicken Paprikash?

“Paprikash” comes from the Hungarian word for paprika, and describes a range of stew-like dishes made with meat, onions, lots of paprika, and sour cream. Tomatoes are not found in the authentic Hungarian dish, which gets all of its red-orange hue from paprika, but you will hardly find a paprikash anywhere in American that does not include tomatoes. Though chicken seems to have been the original meat used in paprikash, lamb, pork and especially veal are also used, and mushrooms make a good meat substitute for vegetarian versions. Traditionally, Chicken Paprikash is served with dumplings, but wide noodles have now become equally common.

The History of Chicken Paprikash

Although it’s agreed that Chicken Praprikash is an authentic Hungarian dish that dates back several centuries, there are no precise details on when it entered the cuisine mainstream. My belief is that, unlike goulash, which was invented by trail herders on the move, Chicken Paprikash originated among the farmers of southern Hungary. This rich, sunny agricultural district supplied the peppers from which paprika is made, and two towns in the region – Kalocsa and Szeged – are known for their excellent paprika. The fact that this originated as a chicken dish also argues for its farm origins. Paprikash, like “coq au vin”, is a dish designed to use up older, tougher birds past their prime – a protein source always available on farms.

It’s All About the Paprika

Paprikash is one of the few dishes in the world that takes its name from a spice – in this case, the spice that became the backbone of Hungarian cuisine. Originally imported from Turkey, the peppers that are dried and ground into paprika have been grown in southern Hungary for nearly 500 years.

In America, paprika comes in two varieties, sweet and hot. In Hungary, where growers and manufacturers blend paprika with the care of vintners blending grapes for wine, there are seven official gradations. From mildest and sweetest to the strongest and spiciest, they are:

- Special Quality

- Exquisite Delicate

- Pungent Exquisite Delicate

- Rose

- Noble Sweet

- Half-Sweet

- Strong

If you want to make paprikash, goulash, or any other dish involving paprika and the jar you have has been sitting around for a year or so because you only use it as a garnish, leave the old stuff on the shelf and buy a fresh can of the high quality imported stuff. The taste difference is well worth the relatively small expense.

How To Make Chicken Paprikash

As I noted earlier, Chicken Paprikash can also be made with lamb, veal, pork, or with a medley of vegetables like mushrooms and carrots. It’s an easy dish to make no matter what meat you choose, and is made essentially the same way, whether you try the original Hungarian Chicken Paprikash recipe without tomatoes or the more familiar version with tomatoes (which Hungarians call Chicken Paprika Stew).

To make Chicken Paprikash, begin by browning onions in a little oil, then add meat, brown, then reduce the heat and add paprika just to warm the spice. Add water or broth – and tomatoes if you’re using them – then cover the pot and left it simmer until the meat is fully cooked and tender.

The final touch is adding the sour cream just before serving. Here, I deviate from standing procedure a bit. To me, one of the joys of paprikash is the deep, jewel-like ruby-red color of the sauce. I like to let that shine. So I leave the sour cream out, ladle the paprikash over individual bowls of wide noodles, and finish each with a dollop of sour cream, which I’ve let warm to room temperature and stirred well so it won’t come off the spoon in a cold, unattractive lump.

For a final touch, garnish each bowl of paprikash with little chopped parsley and there you have it… the color of the flag of Hungary: red, white and green! Enjoy!

Let Shisler’s Cheese House help you create this succulent, dish with our supply of Paprikash Sauce from